Source: Washington Post

Feb 2, 2023

By Nilo Tabrizy, Atthar Mirza and Babak Dehghanpisheh

Four months into Iran’s uprising, protesters are still in the streets. Authorities are still answering with violence and intimidation.

Nowhere is this bloody stalemate more evident than in the southeastern province of Sistan-Baluchestan, which endured the single deadliest government crackdown on protesters in late September and is now the site of weekly demonstrations after Friday prayers.

Video posted to social media on Jan. 20 shows a large group of protesters in Zahedan, Iran, who continue to protest every Friday after prayers. (Video: Haalvsh/Telegram)

“It’s one of the biggest centers of protests in Iran right now,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran.

The Washington Post analyzed more than 100 videos and photographs, interviewed eyewitnesses and human rights observers, and reviewed data collected by conflict monitoring groups over 17 weeks of protests — to better understand the intensity and sophistication of the government crackdown, and the persistence of the protesters.

Visual evidence shows with new clarity how security forces are operating in the region, as Iran’s feared Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) works in tandem with riot police and plainclothes agents to violently suppress demonstrations — carrying out arbitrary arrests, indiscriminate beatings and, in some cases, opening fire on civilians.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, has called protesters “traitors,” accused them of “rioting,” and blamed the United States and Israel for instigating the unrest. A spokesman for Iran’s United Nations mission in New York did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

The majority of the population in the province is ethnic Baluch, a predominantly Sunni minority that has faced neglect and discrimination for decades at the hands of Tehran’s theocratic Shiite government. But the resilience and desperation here speak to the enduring power of the nationwide protest movement, which began in mid-September after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in the custody of Iran’s “morality police.”

“We have no future, no hope,” one protester told The Post. “Life has become so difficult, we think to ourselves even if we get killed here maybe there will be a better future for our children tomorrow.”

Deadly force

On Sept. 30, or “Bloody Friday,” at least 66 people were killed by security forces in the provincial capital of Zahedan, according to Amnesty International. If the goal was to crush the uprising, it has had the opposite effect. Protesters stayed home the week after the incident, but have been back in the streets every Friday since.

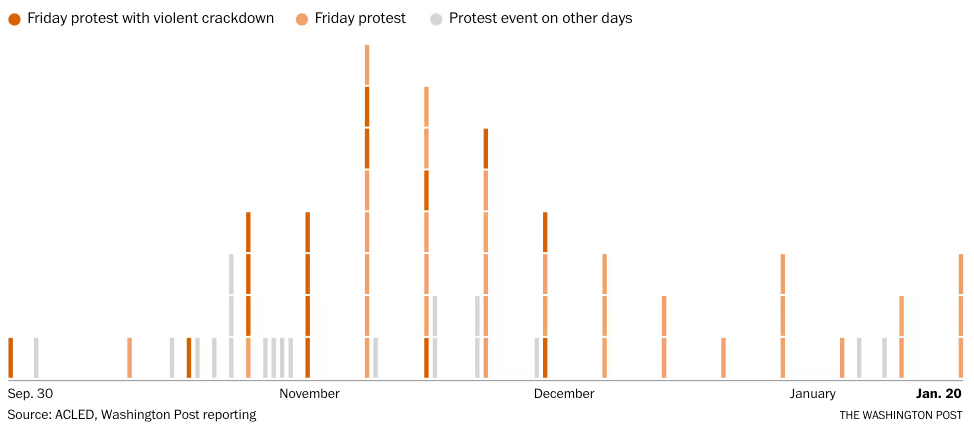

On nearly half of the weeks, protests have been met with a forceful crackdown by security forces, resulting in deaths, injuries or mass arrests. At least 29 people have been killed during Friday protests since Oct. 28, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which verifies reports from local and international sources.

Massacre in Zahedan triggered weekly protests and more violent crackdowns

Protest events per day in the Sistan-Baluchestan province of Iran.

“There hasn’t been a single Friday where people haven’t expressed themselves on the streets,” said one protester, a shop owner in Zahedan. Like others interviewed for this story, he spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect his own safety.

“Each Friday, their fear becomes less,” he added.

Many of the protesters are inspired by Molavi Abdol Hamid, the most prominent Sunni cleric in the country, who has used his weekly sermons at the Makki Mosque in Zahedan to condemn the heavy-handedness of security forces and the abuse of detainees. The largest protests are in Zahedan, near the area where forces opened fire on Bloody Friday, but they have also spread to smaller towns.

The deadliest incident since Bloody Friday took place on Friday, Nov. 4, in Khash, 110 miles south of Zahedan. Video verified by The Post shows a crowd of men and young boys gathered outside a local government office, throwing rocks and chanting anti-government slogans. Gunfire is audible throughout the video, likely from “someone using a high-powered rifle,” according to Steven Beck, a forensic gunshot analyst.

Then, three loud shots ring out. A protesters falls to the ground and the crowd begins to scatter, revealing four people lying motionless on the ground. At least 18 people were reportedly killed in Khash that day, including four minors, according to Haalvsh, a local human rights organization.

The Post could not independently confirm the death toll, but graphic videos uploaded to Telegram show chaotic scenes at the hospital. Injured people, including at least two small boys, are brought in with blood-soaked clothes, suffering from chest, neck and head wounds. Three people are brought in completely limp and immobile on stretchers, their bodies covered with cloth.

Farzin Kadkhodaei, a human rights activist from Sistan-Baluchestan who now lives in Europe, said most demonstrators try to avoid hospitals because they are under government surveillance.

“Even if someone is hit with a bullet, they don’t report it because there’s a high chance that security forces will find them and arrest them,” Kadkhodaei said. “People usually tend to their injuries at home,” he added, saying sympathetic doctors and nurses now make secret house calls.

Video uploaded on Nov. 18 shows a man with an automatic firearm shooting from the roof of a shopping mall, identified by locals as a “military sniper.” (Video: Haalvsh/Telegram)

Two weeks later, at a Friday protest in Zahedan, a video uploaded to Telegram shows a man with a firearm on the roof of a shopping mall, identified by Haalvsh as a “military sniper.” Brian Castner, a weapons investigator with Amnesty International, said the firearm is likely a Kalashnikov rifle, which can only shoot live ammunition.

“The main issue involves how he shoots it into the air,” Castner said. “It is not possible to use fully automatic weapons in an appropriate way in a policing situation at all.”

‘Military occupation’

As Friday demonstrations have continued, the foot soldiers of Iran’s vast and multilayered security state have fanned out across Sistan-Baluchestan, along with armored vehicles.

“The general population is very angry and lives pretty much under military occupation,” Ghaemi said.

One of the prominent uniformed units in the province is the Law Enforcement Command of the Islamic Republic of Iran, also known as FARAJA. This police force is often among the first to be deployed during protests and wears distinctive black uniforms, according to Afshon Ostovar, an associate professor at the Naval Postgraduate School who focuses on Iranian national security.

Multiple large black vans with the official emblem of FARAJA on their doors can be seen in a video posted on Nov. 25 in Zahedan. That same day, Haalvsh reported that groups of people were arrested across the city.

“When they begin arresting people, they put them in these vans and take them to various detention centers,” said Mohammad Hossein Ziya, an editor at the Iranian online news organization Sahamnews who reviewed the video.

Mass arrests remain a central feature of the government crackdown — an estimated 20,000 people have been detained nationwide since the start of the unrest, according to the activist news agency HRANA, though reporting restrictions make the exact toll impossible to verify.

A 40-year-old health-care worker in Zahedan who has been protesting since September explained to The Post how the strategy of security forces shifted as demonstrators began to gather in smaller groups.

“Instead of shooting people, when security forces saw that the protests were intentionally dispersed throughout the city, they saw that was harder to control them,” he said. “In response, they began arresting large groups of people, punishing them, charging them with waging war against God and sentencing them to death.”

On Jan. 5, Iran International reported that at least 100 Baluch protesters were arrested in Zahedan in a joint effort between the police and the IRGC, Iran’s most fearsome security unit.

Their presence is “a signal that police forces and their tactics are insufficient at quelling unrest,” Ostovar said. “So the regime turns to more violent and militarized means.”

A video from Nov. 25 in Khash, Iran, shows Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and anti-riot police units on a bridge adjacent to the Alkhalil Central Mosque. (Video: Haalvsh/Telegram)

A video from Nov. 25 in Khash shows armed units on a bridge adjacent to the Alkhalil Central Mosque. The person filming identifies the units as “IRGC special forces” and the khaki uniforms and boots match the standard dress of the Salman Corps, the provincial unit of the IRGC, according to Ostovar. The men are standing on a truck with a firearm mounted on the front.

“The larger weapon mounted on the truck is likely a PKM-style machine gun,” Castner said. “The man standing in the back of the truck has a rifle over his shoulder, probably an AK variant.” He confirmed that both weapons can only fire live ammunition.

A video shared online on Friday, Nov. 11, in Zahedan shows security forces in similar tan-colored uniforms occupying a high school as shots ring out in the distance.

Starting in late November, the health-care worker says he began seeing fewer injuries from live ammunition and more from metal pellets — less lethal, but still capable of terrible damage.

“They contain pieces of metal and when they enter the body, they create multiple wounds,” he said, noting that some protesters have been blinded.

The goal, he believes, is to wear down the local population: “They changed their tactics, not because they’re retreating, but because the tactic of mass murdering people tarnished their image. So [now] they use metal pellets instead.”

‘They hide and wait’

While Iranian police and IRGC forces represent the tip of the spear in Sistan-Baluchestan, there is another more insidious dimension to the crackdown.

Videos posted to Telegram by Haalvsh show many examples of men in local Baluchi dress involved in policing activities. Mark Pyruz, an Iranian security expert, believes these plainclothes forces most likely belong to the Intelligence Ministry, the intelligence wing of the IRGC, or the Basij, the guards’ volunteer paramilitary wing.

“About 500 meters away from the mosque, they hide and wait, create a checkpoint and block the roads,” said a 53-year-old man who protests every Friday. “People can’t even return to their own homes.”

“We think that they’re from our communities and we go towards them,” he continued. “Then they take us and arrest us.”

Video uploaded on Nov. 25 shows a man dressed in local Baluchi clothing beating protesters. The original video was uploaded in slow motion. (Video: Haalvsh/Telegram)

A video filmed from a rooftop on Friday, Nov. 25, shows multiple people outside the Madras Pharmacy in Zahedan. A man dressed in local clothing is seen beating detainees on the ground while an armed man in tan fatigues stands by.

Video shared online on Nov. 25 shows a confrontation between security forces and protesters in Zahedan, Iran. (Video: Haalvsh/Telegram)

Another video posted on the same day appears to show a confrontation between protesters and security forces in front of the Pastoor Pharmacy, next to the Makki Mosque. Mosque security guards in bright green vests act as a barrier between the two groups.

A man in dark Baluchi dress holds a weapon that he briefly aims at the crowd, identified by Castner as a 38mm grenade launcher, which is generally used to fire tear gas canisters. Behind the man are security forces in khaki uniforms who observe the scene without interfering.

Another man in white clothes and a dark vest appears to be filming the crowd of protesters on a phone, a common surveillance tactic in Iran.

“Security forces are still monitoring people, filming them at checkpoints, at protests,” Kadkhodaei said. “It’s almost like the forces have an album of residents’ photographs because they’ve been so intensely surveilling them.”

A man in uniform begins to fire tear gas into the crowd. Each Friday, though, the crowds return to the streets.

“We have rights in this country, but until now, we haven’t even received the smallest form of human rights,” a protester told The Post. “We’re ready to sacrifice ourselves today for our children tomorrow.”

By Nilo TabrizyNilo Tabrizy is a video reporter for The Washington Post's Visual Forensics team. Before joining The Post, she worked as a video journalist at the New York Times, where she covered Iran, race and policing, and abortion access. She was also a reporter at Vice News covering drug policy and harm reduction. Twitter

By Atthar MirzaAtthar Mirza is a reporter specializing in graphics, animation and interactive storytelling. Twitter